INTRODUCTION

Airway trauma may be life threatening, immediately or within several hours after acute injury. Although, laryngotracheal injuries represent less than 1% of all traumatic injuries, they account for more than 75% of immediate mortality.6 Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of blunt trauma to the airway, with hanging as a method of attempting suicide increasing in incidence.4,6 Because laryngotracheal separation caused by hanging usually results in early death at the scene, the true incidence is unknown.2,3,6

CASE PRESENTATION

We would like to present the case of a 40-year-old male patient who presented to the university hospital after attempted hanging. He was reasonably fit and healthy with a background history of depression. He was witnessed to hang from a tree at a height of about 12 feet. He was brought to the hospital in the ambulance by the paramedics.

On presentation in accident & emergency department (A&E), he was fully alert with glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 15/15. His cervical spine was already stabilized in hard collar with triple in line immobilization. He was maintaining his airway but was dyspneac and tachypneac. His breathing was paradoxical with oxygen saturation of 89-92% on room air. The most important examination findings were that he was aphonic most probably due to laryngeal injury and quadriplegic most probably due to cervical spine injury. He was gradually getting tired because of dyspnea and tachypnea.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and airway was not considered at this point, as the patient was desaturating already and it was decided to intubate him as he was getting tired. Prior to intubation, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) team did a quick nasendoscopy but could not visualize anything properly as it was a bloody field. It was fully recognized that it will be most probably difficult intubation due to altered anatomy secondary to most probable laryngeal injury as the patient was aphonic, so a proper plan was made for intubation with ENT team on stand by. Plan A was to do routine intravenous induction with modified laryngoscopy, using glidescope with manual in line neck stabilisation. Plan B was to perform quick tracheostomy, if plan A fails and for this, ENT team was ready scrubbed up on stand by to perform surgical tracheostomy straight away if needed.

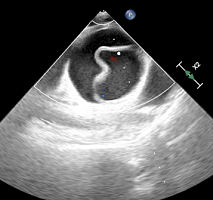

Plan A was initialized and patient was induced intravenously. The patient was very easy to ventilate with bag and mask. When GlideScope was used, the view obtained was very difficult due to bloody field and altered anatomy as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GlideScope Image of Laryngeal Inlet.

The view was 2A (as per Cormack & Lehane), so the bougie was passed through the laryngeal inlet but the bougie was seen to be subcutaneous just under the skin after going through the laryngeal inlet, so it was taken out. The patient was bag and mask ventilated for few seconds and then a second attempt was made to insert the bougie using glidescope, but same thing happened again and the bougie went through the laryngeal inlet but was again seen as subcutaneous just under the skin. This confirmed the laryngeal injury (possibly transection), which was suspected initially as well due to aphonia. The patient was ventilated again with bag and mask for few seconds and this time, laryngoscopy with glidescope was attempted by a senior anaesthetist, bougie was again inserted and this time, it went in to the trachea and the endotracheal tube was inserted over the bougie successfully. The patient was kept anaesthetized using propofol infusion and was taken to the CT scanner for having CT scan of the brain and neck. The CT scan showed no brain injury, fracture of the C2 vertebral pars inter-articularis along with facet joint dislocation between C2 and C3 vertebrae. It also showed antero listhesis of C2 vertebra over C3 vertebra along with respective spinal canal stenosis. In addition, there was surgical emphysema with locules of free gas in the retropharyngeal and right carotid spaces.

The patient then went straight to theatre and underwent panendoscopy. Operative findings included complete transection of epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds along with full thickness tears to lateral pharyngeal wall but with intact posterior pharyngeal wall. Esophagus was intact also. The patient then underwent laryngophayngeal repair and tracheostomy.

The patient was eventually sent to the neuro-rehabilitation centre for having neuro-rehabilitation with tracheostomy in situ.

DISCUSSION

Laryngotracheal injury is a rare injury being responsible for less than 1% of the trauma cases seen in most major centers.7,8 This is due to many factors, including rapid death at scene due to asphyxia, anatomical protection provided by sternum and mandible8 and lack of diagnosis of minor airway injuries in victims of major trauma by hospital staff.9

The mechanism for laryngotracheal injury after hanging may be multifold. Sudden neck extension, fixation of the larynx and anteroposterior compression of the tracheal rings result in shearing forces tearing the cricotracheal membrane.10 Direct upward pressure from hanging elevates the larynx superiorly resulting in separation of larynx and trachea.11

Similarly, the extent and location of blunt laryngotracheal trauma is determined by several factors.12 In one review, majority of the injuries occurred above the fourth tracheal ring (88%).13However, penetrating and bullet wounds can occur in any part of the cervical trachea.14 Cricoid facture can occur which can further cause recurrent laryngeal nerve injury compromising the airway lumen even further. In our case, the patient did not suffer laryngotracheal injury. Infact, he had a total laryngeal injury including complete transection of epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds.

Admitted patient with laryngotracheal injury present with specific signs including skin abrasions over anterior neck, dyspnea, hoarseness, subcutaneous crepitus, haemoptysis and dysphagia,15but their presence is variable12,13,16,17 according to the extent of injury. Surgical emphysema may develop hours after the initial injury.18.19 Hanging can also result in cervical spine injuries resulting in hemiplegia, quadriplegia, cranial nerve deficits, horner’s syndrome and neurogenic shock. Our patient was dyspnoec and tachypnoec at presentation with minimal desaturation. However, he was aphonic and quadriplegic due to laryngeal and cervical spine injury respectively.

Investigation and management of a patient with laryngotracheal injury is dependent on the airway status of the patient at arrival in the hospital and the presence of other associated injuries.13 Airway control with cervical spine protection is always the priority. Chest and neck X-rays may demonstrate subcutaneous emphysema or distortion of the laryngotracheal air column.

6-A CT scan has proved beneficial in differentiating between the patients with blunt laryngotracheal trauma requiring conservative management or surgical exploration.20,21

Fibreoptic endoscopic examination of the upper airway may be useful to evaluate the site and extent of airway injury and also enables tracheal intubation while minimizing the risk to the potentially damaged cervical spine.22 However, it may be technically difficult to perform fibreoptic endoscopy due to bleeding, debris and anatomical disruption. It can also result in airway obstruction.12

Tracheostomy is the method of choice for airway management in an acutely injured patient with neck trauma, as attempts at tracheal intubation may result in creation of a false passage, compromising the airway further. Rapid deterioration of the patient, if occurs, may also necessitate tracheostomy.23 Alternatively, femoral-femoral cardiopulmonary bypass can be considered in case of any emergency.14 After airway is established, surgical repair should be undertaken as soon as possible. Early repair within 48 hours shows improved outcomes with respect to airway and voice and also lower incidence of subglottic stenosis.24,25

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONSENT

Consent has been taken from the patient for purpose of using patient photographs for publication in print or on the internet.